Neurological Differences Between OCD and Typical Brain Function

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) affects millions worldwide, manifesting through intrusive thoughts and repetitive behaviors. Recent brain imaging studies have shed light on the neurobiological differences between individuals with OCD and those without the condition.

Research suggests that people with OCD often show differences in brain structure and function, particularly in areas involved in decision making, emotional regulation, and habit formation. These variations can be observed in regions such as the cortex and basal ganglia, which play crucial roles in behavior control and emotional processing.

Brain scans reveal that individuals with OCD may have difficulty learning that situations are safe, potentially explaining their persistent obsessions and compulsions. This challenge in processing safety cues could contribute to the characteristic "loop of wrongness" experienced by those with OCD, making it harder for them to break free from repetitive thoughts and actions.

Understanding OCD

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a mental health condition characterized by recurring, intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental acts (compulsions). These obsessions and compulsions can significantly impact a person's daily life and well-being.

Common obsessions in OCD include:

Fear of contamination

Need for symmetry or order

Intrusive thoughts about harm or violence

Unwanted sexual or religious thoughts

Compulsions often arise as attempts to neutralize or alleviate the anxiety caused by obsessions. Examples include:

Excessive handwashing or cleaning

Repeated checking of locks, appliances, or safety measures

Counting or arranging objects in a specific way

Mental rituals like repeating words or phrases

OCD affects people of all ages and backgrounds. It typically begins in childhood or adolescence, though it can also develop in adulthood. The exact cause of OCD is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, environmental, and neurobiological factors play a role.

Brain imaging studies have shown differences in neural activity and structure in individuals with OCD, particularly in regions involved in decision-making, emotional regulation, and habit formation. These findings contribute to our understanding of the disorder's biological basis.

The Neurobiology of OCD

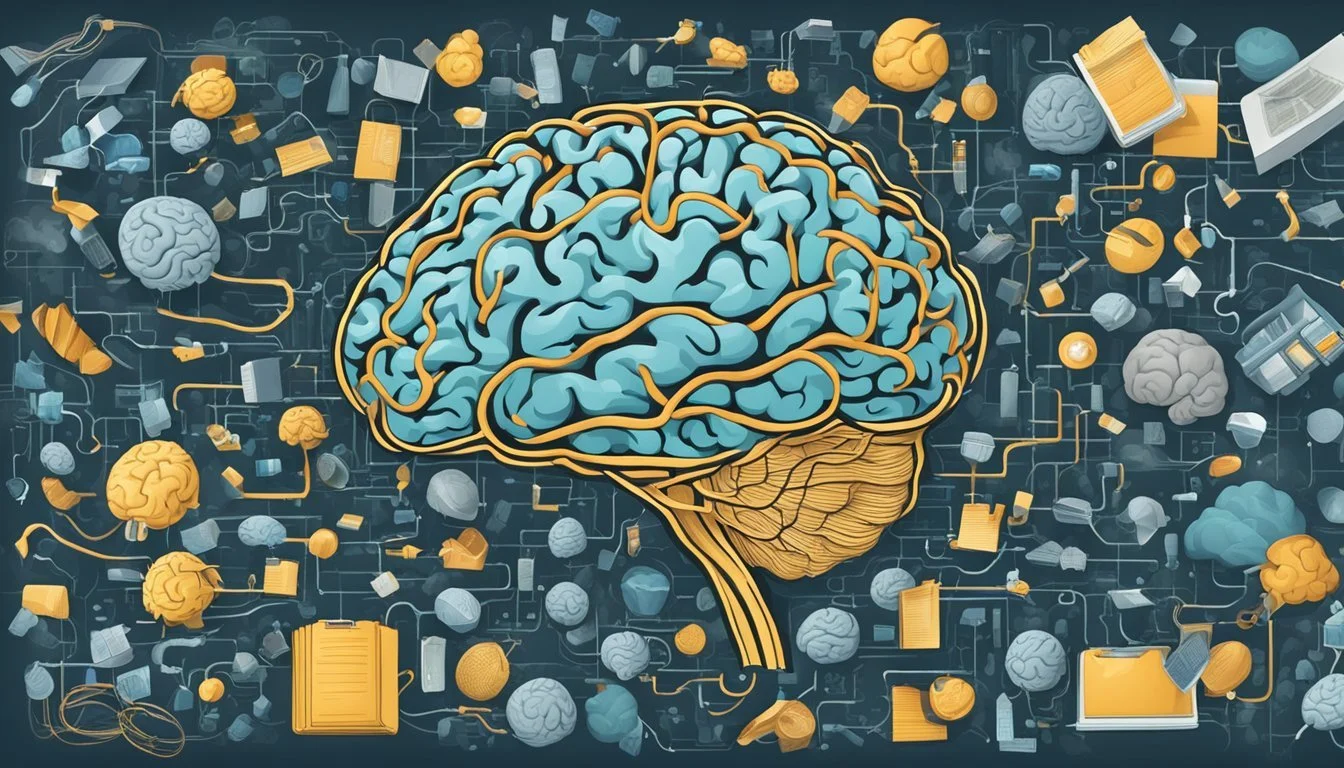

Research has identified specific brain regions and neurotransmitter systems involved in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuroimaging studies reveal structural and functional differences between OCD and healthy brains.

Brain Regions Implicated in OCD

The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and caudate nucleus show increased activity in OCD patients. The OFC is involved in decision-making and behavior regulation. The caudate nucleus plays a role in habit formation and goal-directed actions.

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) also demonstrates hyperactivity in OCD. This region helps regulate emotions and cognitive processes. Structural differences appear in the prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia of OCD brains.

Thalamus abnormalities are observed as well. The thalamus relays information between brain regions. These alterations may contribute to the repetitive thoughts and behaviors characteristic of OCD.

Neurotransmitters and OCD

Serotonin dysfunction is strongly linked to OCD. Many effective OCD treatments target the serotonin system. Low serotonin levels may contribute to obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors.

Glutamate imbalances also play a role. Excessive glutamate signaling is found in OCD brains. This may lead to hyperactivity in the frontal-striatal circuits.

Dopamine irregularities are observed in some OCD patients. Dopamine influences reward-seeking behaviors and habit formation. GABA, the brain's main inhibitory neurotransmitter, shows reduced levels in OCD.

These neurotransmitter imbalances likely interact to produce OCD symptoms. Understanding these neurobiological factors aids in developing targeted treatments for the disorder.

OCD in Different Life Stages

Obsessive-compulsive disorder manifests differently across age groups. Genetic factors play a role in its development and expression throughout life stages.

Pediatric OCD

Childhood-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder typically emerges between ages 8-12. It affects 1-2% of children and adolescents. Common obsessions include contamination fears and a need for symmetry or order.

Compulsions often involve excessive handwashing, checking, or arranging objects. Pediatric OCD can significantly impact a child's academic performance and social relationships.

Treatment usually combines cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with family involvement. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may be prescribed in moderate to severe cases.

Early intervention is crucial for better long-term outcomes. Pediatric OCD often persists into adulthood if left untreated.

Adult OCD

Adult OCD affects about 2% of the population. Symptoms may intensify during periods of stress or major life changes. Common obsessions include fears of harming others or contracting diseases.

Compulsions can involve mental rituals, excessive cleaning, or hoarding. Adult OCD frequently co-occurs with depression and anxiety disorders.

Treatment typically includes CBT, particularly exposure and response prevention (ERP). Medication, such as SSRIs or clomipramine, may be prescribed.

Many adults with OCD experience fluctuations in symptom severity over time. Maintaining treatment adherence is important for long-term management.

Genetic Considerations in OCD

OCD has a strong genetic component. First-degree relatives of individuals with OCD have a 4-5 times higher risk of developing the disorder.

Twin studies suggest OCD heritability ranges from 45-65%. Specific genes linked to OCD risk include those involved in serotonin and glutamate signaling.

Environmental factors interact with genetic predisposition. Stressful life events can trigger OCD onset in genetically susceptible individuals.

Genetic testing is not currently used for OCD diagnosis. However, understanding genetic factors may help develop targeted treatments in the future.

Diagnostic Procedures

Diagnosing OCD involves clinical assessments and advanced neuroimaging techniques. These methods help distinguish OCD from other mental health conditions and provide insights into brain structure and function.

Clinical Diagnosis of OCD

Clinicians use the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria to diagnose OCD. They assess the presence of obsessions and compulsions, their time consumption, and impact on daily functioning.

A thorough patient history and psychiatric evaluation are crucial. Clinicians may use structured interviews and rating scales to measure symptom severity. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) is a common tool.

Differential diagnosis is important to rule out other disorders with similar symptoms. This may include anxiety disorders, depression, or tic disorders.

Role of Neuroimaging in OCD Diagnosis

Neuroimaging techniques provide valuable insights into the OCD brain. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) reveals structural differences in specific brain regions.

Functional MRI (fMRI) shows altered brain activity patterns in OCD patients. It highlights hyperactivity in the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and striatum.

Voxel-Based Morphometry (VBM) analyzes brain tissue density. Studies using VBM have found gray matter abnormalities in OCD patients.

Brain scans are not used for routine diagnosis but aid in research and understanding OCD neurobiology. They may help in treatment planning and monitoring response to interventions like cognitive-behavioral therapy or medication.

Comparing OCD and Non-OCD Brains

Brain imaging studies have revealed significant differences between individuals with OCD and those without the disorder. These variations involve both structural and functional aspects of the brain.

Structural Differences

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans show distinct structural disparities in OCD brains. The orbitofrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex often display increased gray matter volume. Conversely, the parietal cortex and posterior cingulate region may exhibit reduced gray matter.

White matter abnormalities are also evident in OCD patients. Diffusion tensor imaging studies indicate altered connectivity in major white matter tracts, particularly those connecting frontal areas to subcortical structures.

The caudate nucleus, part of the basal ganglia, frequently shows enlarged volume in OCD brains. This structure plays a crucial role in movement control and cognitive processes.

Functional Variations

Functional MRI studies highlight differences in brain activity patterns between OCD and non-OCD individuals. OCD brains typically show hyperactivity in the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and caudate nucleus during symptom provocation or cognitive tasks.

PET scans reveal elevated cerebral glucose metabolic rates in OCD patients, particularly in the orbitofrontal cortex and caudate nucleus. This increased metabolic activity correlates with symptom severity.

Regional cerebral blood flow also differs in OCD brains. Higher blood flow is observed in the frontal cortex and basal ganglia, while lower flow is seen in posterior brain regions.

These functional variations suggest altered neural circuitry in OCD, affecting decision-making, error processing, and behavioral inhibition.

Treatment Approaches

Effective treatments for OCD target both the brain and behavior. Several evidence-based options can help reduce symptoms and improve quality of life for those affected.

Psychotherapeutic Interventions

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with exposure and response prevention (ERP) is the gold standard psychotherapy for OCD. ERP involves gradual exposure to feared situations while resisting compulsions. This helps retrain the brain's response to anxiety triggers.

CBT also addresses distorted thought patterns that fuel OCD behaviors. Patients learn to challenge obsessive thoughts and develop healthier coping strategies.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is another promising approach. It focuses on accepting intrusive thoughts without judgment while committing to value-driven behaviors.

Pharmacotherapy

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the first-line medication treatment for OCD. These drugs increase serotonin levels in the brain, which helps regulate mood and anxiety.

Commonly prescribed SSRIs include fluoxetine, sertraline, and paroxetine. Higher doses are often needed compared to depression treatment.

For some patients, adding antipsychotic medications can boost SSRI effectiveness. Clomipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant, may be used for treatment-resistant cases.

Surgical and Neuromodulation Therapies

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a surgical option for severe, treatment-resistant OCD. It involves implanting electrodes in specific brain regions to modulate neural circuits involved in OCD.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a non-invasive technique that uses magnetic fields to stimulate brain areas. It may help improve cognitive flexibility and reduce OCD symptoms.

Gamma knife radiosurgery is being studied as a potential treatment. This precise radiation therapy targets specific brain areas without invasive surgery.

Brain Functionality and Connectivity

The neural networks in OCD brains show distinct patterns of connectivity and functionality compared to typical brains. These differences manifest in altered communication between brain regions and impaired inhibitory control.

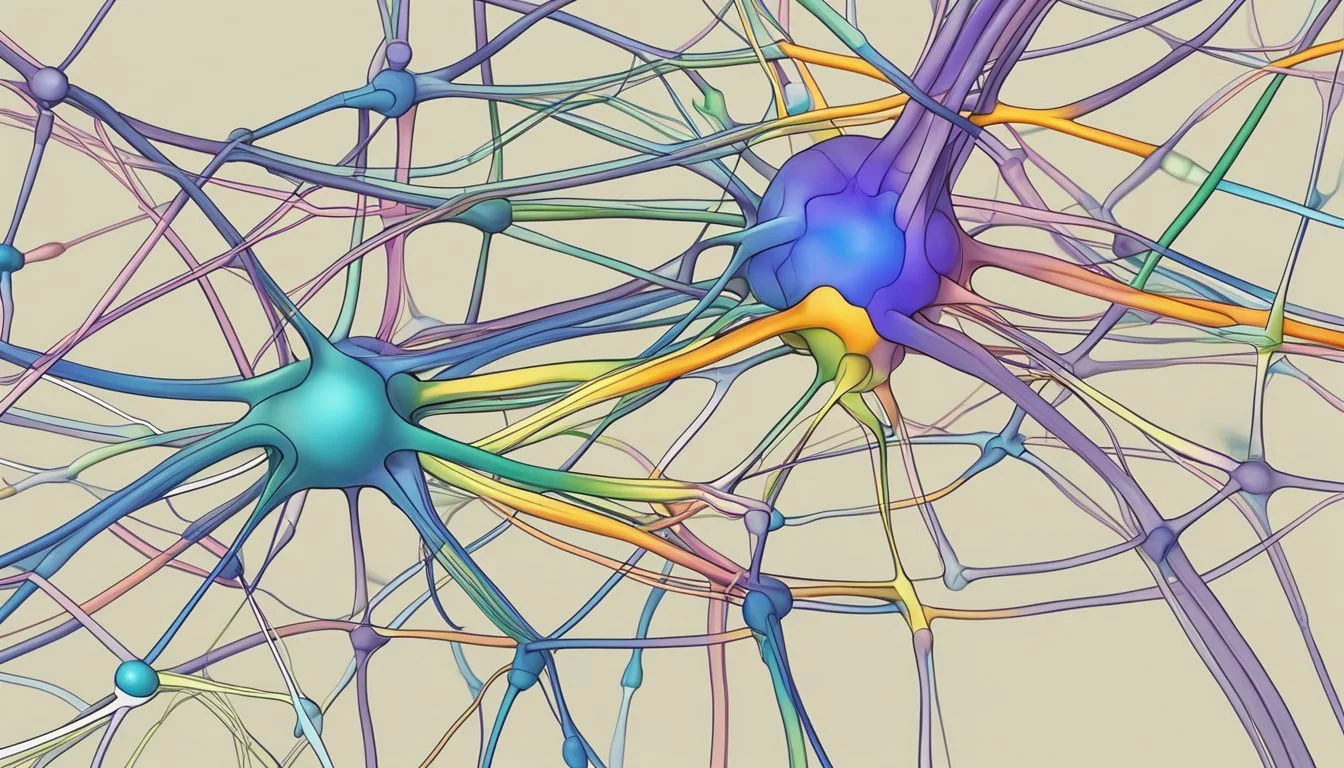

Connectivity in OCD Neural Networks

Functional connectivity studies reveal disrupted communication patterns in OCD brains. Resting-state functional MRI scans show abnormal connectivity between frontal cortex areas and the striatum. This fronto-striatal circuit plays a key role in OCD symptoms.

Symptom severity often correlates with the degree of connectivity disruption. More severe OCD symptoms tend to align with greater abnormalities in brain network hubs. These hubs act as central connection points between different brain regions.

Treatment can help normalize some of these connectivity issues. Successful interventions may restore more typical patterns of communication between frontal and striatal regions.

The Role of Inhibition

Inhibitory control deficits are a hallmark of OCD. Functional imaging shows reduced activation in brain areas responsible for inhibition during relevant tasks. This hypoactivation likely contributes to difficulties suppressing intrusive thoughts and compulsive behaviors.

OCD brains also exhibit decreased functional connectivity between key regions during cognitive tasks requiring inhibition. This impaired neural communication may underlie the persistent nature of OCD symptoms.

Some inhibition-related brain changes appear to improve with effective OCD treatment. However, certain alterations in cognitive and neural functioning persist even after symptom reduction.

Impact of OCD on Life Quality

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) significantly affects a person's quality of life. It can disrupt personal relationships, work performance, and daily activities.

Individuals with OCD often struggle with unwanted thoughts and repetitive behaviors. These intrusive thoughts and compulsions can consume hours of their day, leaving little time for other pursuits.

OCD frequently co-occurs with depression, further impacting overall well-being. This comorbidity can intensify the challenges faced by those with OCD.

The Global Burden of Disease study ranks OCD as one of the top 10 most disabling mental health conditions worldwide. Its impact extends beyond the individual to families and communities.

Safety concerns are common among people with OCD. They may engage in excessive checking behaviors or avoid situations perceived as dangerous, limiting their participation in everyday activities.

OCD can interfere with education and career advancement. Students may struggle to complete assignments, while professionals might face difficulties meeting deadlines or interacting with colleagues.

Relationships often suffer as OCD symptoms demand time and attention. Partners and family members may feel frustrated or neglected, leading to increased tension and conflict.

Sleep disturbances are frequently reported by individuals with OCD. Intrusive thoughts can make it difficult to fall asleep or stay asleep, resulting in daytime fatigue and reduced productivity.

Associated Conditions and Disorders

OCD often coexists with several related conditions that share similar features and underlying neurobiological mechanisms. These associated disorders can complicate diagnosis and treatment.

Hoarding and OCD

Hoarding Disorder involves excessive acquisition and difficulty discarding possessions, leading to cluttered living spaces. While previously classified as a subtype of OCD, it is now recognized as a distinct condition. Hoarders experience intense distress when parting with items and may have impaired decision-making abilities.

Brain imaging studies show similarities between hoarding and OCD in areas like the anterior cingulate cortex and orbitofrontal cortex. However, hoarders exhibit unique patterns of neural activation during decision-making tasks.

Treatment approaches for hoarding often differ from standard OCD interventions. Cognitive-behavioral therapy focusing on decision-making skills and exposure to discarding items is typically recommended.

Trichotillomania and Skin Picking

Trichotillomania involves recurrent hair pulling, while skin picking disorder is characterized by repetitive picking at skin. Both conditions share features with OCD, including ritualistic behaviors and difficulty controlling urges.

These disorders involve dysfunction in the cortico-striatal circuits, similar to OCD. However, they also show distinct patterns of brain activation during symptom provocation.

Treatment often combines habit reversal training, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and sometimes medication. N-acetylcysteine has shown promise in reducing symptoms for both conditions.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) involves obsessive preoccupation with perceived flaws in physical appearance. Individuals with BDD engage in repetitive behaviors like mirror checking or skin picking.

BDD shares neural abnormalities with OCD in the orbitofrontal cortex and caudate nucleus. However, BDD patients show heightened activation in visual processing regions during facial recognition tasks.

Treatment typically involves cognitive-behavioral therapy with exposure and response prevention, similar to OCD interventions. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are often prescribed to manage symptoms.

Advancements in OCD Research

Recent neuroimaging and genetic studies have revealed new insights into the brain structures and molecular mechanisms involved in obsessive-compulsive disorder. These findings are enhancing our understanding of OCD's underlying biology and paving the way for improved diagnostic and treatment approaches.

Recent Findings from Neuroimaging

Advanced brain imaging techniques have uncovered structural and functional differences in OCD brains. Neuroimaging studies using diffusion tensor imaging have identified altered white matter connectivity in OCD patients. Meta-analyses show consistent reductions in cortical thickness and gray matter volume in regions like the anterior cingulate cortex.

The ENIGMA consortium's large-scale analysis found decreased subcortical volumes in OCD patients, particularly in the hippocampus and pallidum. Functional MRI studies reveal hyperactivity in the orbitofrontal cortex and striatum during symptom provocation.

Researchers have also discovered brain patterns linked to deep brain stimulation effectiveness, potentially allowing more tailored treatment. These neuroimaging advances are improving our ability to diagnose OCD and evaluate treatment responses objectively.

Genetics and Molecular Research

Genetic studies have made significant progress in identifying OCD risk genes. Genome-wide association studies have found variations in genes related to glutamate signaling and synaptic functioning. Twin studies estimate OCD heritability at 40-50%, indicating a strong genetic component.

Epigenetic research shows altered DNA methylation patterns in OCD patients, suggesting environmental factors influence gene expression. Animal models have helped elucidate the role of specific genes like SAPAP3 in compulsive behaviors.

Molecular studies have uncovered dysregulation of neurotransmitter systems, particularly serotonin and dopamine. This research is guiding the development of new pharmacological treatments targeting these pathways.