Preparing for Hoarding Disorder NCLEX: Key Insights for Nursing Students

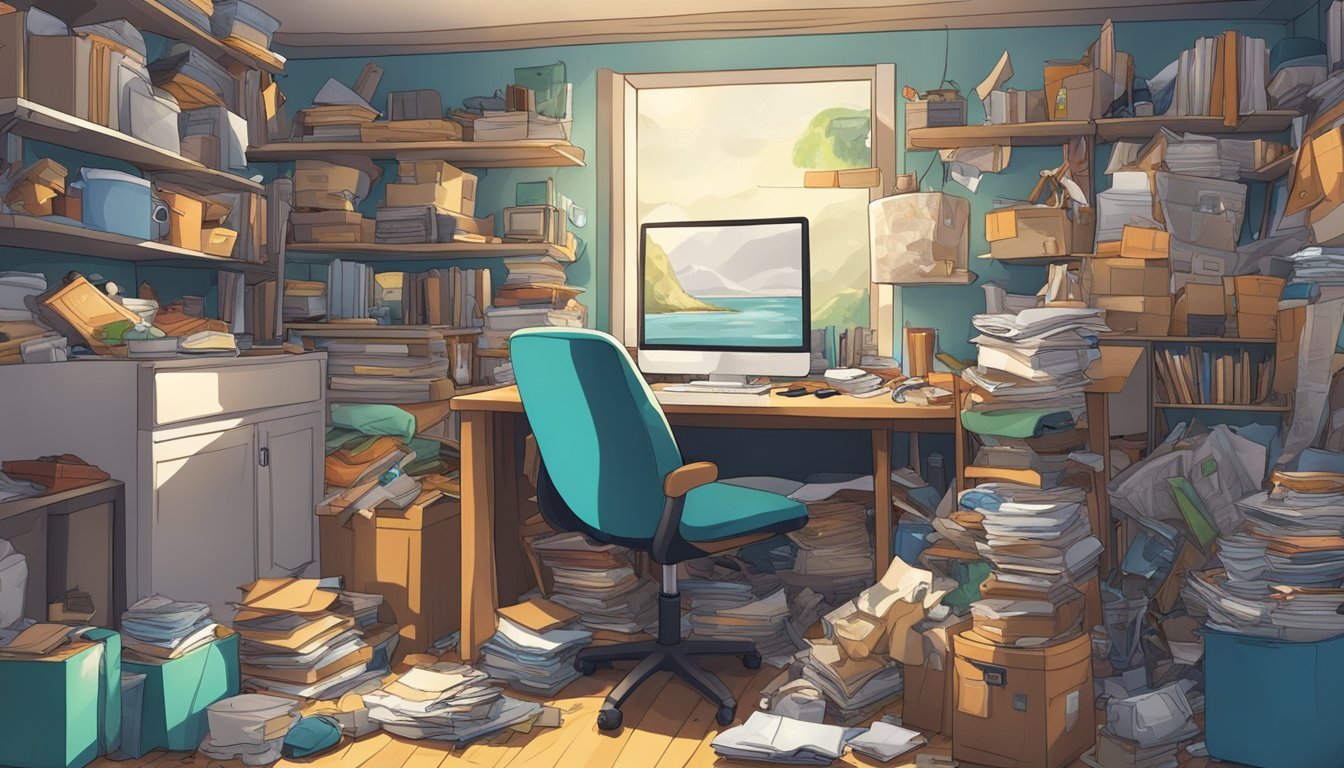

Hoarding disorder is a complex mental health condition characterized by persistent difficulty discarding possessions, regardless of their actual value. This disorder often leads to cluttered living spaces and significant distress for the affected individual and their loved ones.

Hoarding disorder frequently co-occurs with mood and anxiety disorders, including major depressive disorder, social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Understanding these comorbidities is crucial for healthcare professionals when assessing and treating patients with hoarding tendencies.

Treatment for hoarding disorder typically involves a multifaceted approach. This may include cognitive-behavioral therapy, medication management, and support from community agencies. Nurses play a vital role in educating patients and families about the nature of hoarding disorder, emphasizing that recovery is possible with appropriate interventions and support.

Understanding Hoarding Disorder

Hoarding disorder is a complex mental health condition characterized by difficulty discarding possessions and excessive acquisition behaviors. It affects 4-5% of the population and can significantly impact an individual's quality of life, relationships, and living environment.

Definition and Prevalence

Hoarding disorder is defined as persistent difficulty parting with possessions, regardless of their actual value. This results in accumulation of items that clutter living spaces, making them unusable for their intended purposes. The disorder affects approximately 1 in 50 people worldwide.

Individuals with hoarding disorder experience intense distress at the thought of discarding items. They often feel a strong need to save objects and may excessively acquire new possessions. This behavior can lead to unsafe living conditions and impaired social functioning.

Etiology and Risk Factors

The exact causes of hoarding disorder are not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, neurobiological, and environmental factors contribute to its development.

Genetic predisposition plays a role, with studies showing higher rates of hoarding among first-degree relatives of affected individuals. Brain imaging studies have revealed differences in neural activity related to decision-making and emotional attachment to objects in people with hoarding disorder.

Environmental risk factors include:

Traumatic life events

Family history of hoarding

Childhood deprivation

Social isolation

Perfectionism

Comorbid mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), are also common among individuals with hoarding disorder.

Diagnosis Criteria

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) outlines specific criteria for diagnosing hoarding disorder:

Persistent difficulty discarding possessions, regardless of actual value

Perceived need to save items and distress associated with discarding them

Accumulation of possessions that clutter active living areas

Significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning

Hoarding not attributable to another medical condition or mental disorder

Diagnosis requires a comprehensive assessment by a mental health professional, including a thorough history and evaluation of the individual's living environment.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of hoarding disorder can vary, but common features include:

Cluttered living spaces

Difficulty organizing and categorizing possessions

Indecisiveness about what to keep or discard

Emotional attachment to objects

Social withdrawal and isolation

Impaired daily functioning

Individuals may express beliefs about the usefulness or sentimental value of items, even if they appear worthless to others. Safety concerns often arise due to fire hazards, unsanitary conditions, or blocked exits in severely cluttered homes.

Differential Diagnosis

Distinguishing hoarding disorder from other conditions is crucial for proper treatment. Key differential diagnoses include:

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD): While both involve repetitive behaviors, hoarding in OCD is typically driven by specific obsessions rather than attachment to possessions.

Depression: Accumulation of items may occur due to lack of energy or motivation, but without the emotional attachment seen in hoarding disorder.

Dementia: Cognitive decline can lead to collecting behaviors, but these are typically new-onset and not longstanding.

Autism Spectrum Disorder: Special interests may lead to collecting, but without the associated distress or impairment.

Diogenes Syndrome: This condition involves extreme self-neglect and social withdrawal, often in older adults, but may not include emotional attachment to possessions.

Accurate diagnosis is essential for developing an effective treatment plan tailored to the individual's specific needs and challenges.

Impact on Health and Lifestyle

Hoarding disorder significantly affects physical and mental wellbeing, as well as social and occupational functioning. The accumulation of excessive items creates hazardous living conditions and strains relationships.

Physical Health Consequences

Cluttered living spaces pose numerous health risks. Excessive items create tripping hazards, increasing the likelihood of falls and injuries. Dust accumulation exacerbates respiratory issues like asthma and allergies.

Blocked exits impede emergency evacuations, raising fire safety concerns. Pests attracted to clutter can spread diseases. Moldy or expired food items may lead to foodborne illnesses.

Neglected home maintenance results in structural damage, exposing residents to environmental hazards. Limited access to kitchen facilities often leads to poor nutrition and reliance on unhealthy convenience foods.

Mental Health Consequences

Hoarding disorder frequently co-occurs with other mental health conditions. Depression and anxiety are common, exacerbated by feelings of shame and isolation.

Individuals may experience chronic stress from living in cluttered environments. Decision-making difficulties extend beyond hoarding behaviors, impacting daily functioning.

Sleep disturbances are frequent due to uncomfortable living conditions. Cognitive decline may occur from lack of mental stimulation in a chaotic environment.

Self-esteem issues often arise from perceived judgment by others. Some individuals develop agoraphobia, avoiding leaving home due to embarrassment about their living situation.

Social and Occupational Impairment

Hoarding behaviors strain relationships with family and friends. Loved ones may feel frustrated or overwhelmed by the clutter. Social isolation increases as individuals avoid inviting others to their homes.

Maintaining employment becomes challenging due to time spent acquiring and organizing possessions. Tardiness or absenteeism may occur from difficulty navigating cluttered living spaces.

Financial strain results from excessive purchasing and potential property damage. Legal issues may arise from code violations or eviction threats.

Participation in social activities decreases, leading to a shrinking support network. Romantic relationships suffer due to limited space and conflicts over clutter.

Assessment Techniques

Accurate assessment of hoarding disorder requires a multi-faceted approach. Clinicians employ various methods to evaluate the severity, impact, and underlying factors contributing to hoarding behaviors.

Clinical Interview

The clinical interview forms the foundation of hoarding disorder assessment. Clinicians gather detailed information about the patient's acquisition habits, difficulty discarding items, and the resulting clutter. Questions focus on:

• Emotional attachments to possessions • Beliefs about the value or usefulness of items • Distress associated with discarding

Clinicians also explore the functional impact of hoarding on daily life, relationships, and living spaces. Safety concerns, such as fire hazards or fall risks, are addressed. The interview helps identify any co-occurring mental health conditions that may influence hoarding behaviors.

Environmental Assessment

A home visit or photographic evidence provides crucial insights into the extent of clutter. Clinicians evaluate:

• Accessibility of living spaces • Presence of pathways through rooms • Functionality of key areas (kitchen, bathroom, bedroom)

The Clutter Image Rating Scale is often used to visually assess room conditions. This tool presents a series of photographs depicting increasing levels of clutter. Patients or clinicians select images that best represent the current state of different rooms in the home.

Assessment Scales

Standardized scales help quantify hoarding symptoms and track progress over time. Common tools include:

Saving Inventory-Revised (SI-R): Measures difficulty discarding, excessive acquisition, and clutter.

Hoarding Rating Scale (HRS): Assesses clutter, difficulty discarding, excessive acquisition, distress, and impairment.

Activities of Daily Living in Hoarding (ADL-H): Evaluates the impact of hoarding on daily functioning.

These scales provide objective measures of hoarding severity and help guide treatment planning. They also facilitate monitoring of symptom changes throughout the intervention process.

Nursing Interventions

Effective nursing interventions for hoarding disorder require a multifaceted approach. These strategies aim to address the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects of the condition while prioritizing patient safety and well-being.

Cognitive-Behavioral Strategies

Nurses can implement cognitive-behavioral techniques to help patients with hoarding disorder. These strategies focus on challenging and modifying dysfunctional thoughts and behaviors associated with hoarding.

Encouraging patients to question their beliefs about possessions is crucial. Nurses can guide them to evaluate the true value and necessity of items.

Teaching organizational skills helps patients categorize and manage their belongings more effectively. This includes creating sorting systems and establishing decluttering routines.

Exposure exercises, where patients practice discarding items gradually, can be beneficial. Nurses should provide support and encouragement during these challenging tasks.

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing is a patient-centered approach that enhances motivation for change. Nurses use this technique to help patients explore their ambivalence about hoarding behaviors.

Open-ended questions encourage patients to reflect on the impact of hoarding on their lives. This helps them identify personal reasons for change.

Reflective listening allows nurses to demonstrate empathy and understanding. It builds trust and rapport with patients.

Affirming patients' strengths and efforts reinforces their ability to make positive changes. Nurses should highlight small successes to boost confidence.

Harm Reduction Approach

A harm reduction approach focuses on minimizing risks associated with hoarding while respecting patient autonomy. This strategy is particularly useful when patients are resistant to treatment.

Nurses should assess and address immediate safety concerns. This includes creating clear pathways, ensuring proper ventilation, and removing fire hazards.

Collaborating with patients to establish "clutter-free zones" in their living spaces can improve functionality and safety. Start with small, achievable goals.

Educating patients about health risks associated with excessive clutter is essential. Provide information on hygiene, fall prevention, and pest control.

Multidisciplinary Team Approach

Hoarding disorder often requires a coordinated effort from various healthcare professionals. Nurses play a crucial role in facilitating this multidisciplinary approach.

Collaborating with mental health specialists ensures comprehensive psychological support. Regular consultations with psychiatrists or psychologists may be necessary.

Occupational therapists can assist in developing practical skills for daily living and home management. Nurses should coordinate with them to reinforce these skills.

Social workers may help address broader issues such as housing concerns or legal matters. Nurses can act as liaisons between patients and social services.

Family involvement, when appropriate, can provide additional support. Nurses should educate family members about hoarding disorder and how to assist their loved ones.

Pharmacological Therapies

Medication can play a role in treating hoarding disorder, particularly when combined with cognitive-behavioral therapy. While research is ongoing, certain pharmacological approaches have shown promise in managing symptoms.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

SSRIs are often considered first-line medication for hoarding disorder. These drugs work by increasing serotonin levels in the brain, which may help reduce compulsive behaviors and anxiety associated with hoarding.

Fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline have been studied for hoarding symptoms. Some patients report reduced urges to acquire items and improved ability to discard possessions. However, response rates vary, and effects may be modest compared to their efficacy in treating other anxiety disorders.

SSRIs typically require 8-12 weeks at therapeutic doses to show benefits. Side effects can include nausea, sleep disturbances, and sexual dysfunction. Regular follow-ups with a prescribing physician are important to monitor progress and adjust dosages as needed.

Other Medication Options

When SSRIs prove ineffective, alternative medications may be considered. Venlafaxine, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, has shown some efficacy in treating hoarding symptoms.

Stimulants like methylphenidate might help improve attention and decision-making in individuals with hoarding disorder. These medications can enhance focus and reduce impulsivity, potentially aiding in organizing and discarding items.

Antipsychotics are sometimes prescribed as augmentation therapy. Risperidone or quetiapine may be added to an SSRI regimen to boost its effectiveness. However, these medications carry risks of metabolic side effects and require careful monitoring.

Glutamate-modulating drugs like memantine are being explored as potential treatments. Early studies suggest they may help reduce hoarding behaviors, but more research is needed to confirm their efficacy and safety profile.

Legal and Ethical Considerations

Treating hoarding disorder involves complex legal and ethical issues. Healthcare providers must navigate challenges related to patient autonomy, safety concerns, and confidentiality while advocating for client rights.

Involuntary Treatment

Involuntary treatment for hoarding disorder raises significant ethical dilemmas. In severe cases where living conditions pose immediate health and safety risks, healthcare providers may consider involuntary interventions.

These actions must balance respect for patient autonomy with the duty to protect individuals from harm. Legal processes, such as court-ordered cleanouts, may be necessary in extreme situations.

Providers should exhaust all voluntary treatment options before pursuing involuntary measures. Obtaining informed consent and involving the patient in decision-making remains crucial whenever possible.

Confidentiality Issues

Maintaining patient confidentiality is essential in hoarding disorder treatment. Healthcare providers must protect sensitive information while addressing potential risks to the patient and others.

HIPAA regulations govern the sharing of patient information. Providers should only disclose necessary details to appropriate parties involved in the patient's care.

Exceptions to confidentiality may arise when there are imminent safety risks. In such cases, providers may need to alert authorities or family members.

Clear communication with patients about confidentiality limits is crucial. This helps build trust and encourages open dialogue during treatment.

Advocacy for Client Rights

Healthcare providers play a vital role in advocating for the rights of individuals with hoarding disorder. This includes ensuring access to appropriate treatment options and support services.

Providers should educate patients about their legal rights and available resources. This may involve connecting them with legal aid services or social workers.

Advocating for fair housing practices is often necessary. Providers can work with landlords or housing authorities to prevent eviction and secure safe living conditions.

Supporting clients in decision-making processes helps preserve their autonomy. Providers should empower patients to make informed choices about their treatment and living situations.

Patient Education and Support

Effective patient education and support are crucial for managing hoarding disorder. These elements help individuals understand their condition, develop coping strategies, and access necessary resources.

Educational Materials

Nurses provide patients with informative leaflets and brochures about hoarding disorder. These materials explain symptoms, causes, and treatment options in clear, accessible language. Visual aids like diagrams and charts illustrate the impact of hoarding on daily life.

Online resources, including reputable websites and educational videos, offer additional information. Patients receive guidance on how to recognize problematic behaviors and implement organizational strategies. Nurses may also recommend books written by experts in the field.

Personalized educational plans tailored to each patient's needs and literacy level ensure better comprehension and retention of information.

Support Groups and Therapy

Support groups offer a safe space for individuals with hoarding disorder to share experiences and coping strategies. These groups can be in-person or online, providing flexibility and accessibility.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is a primary treatment approach. It helps patients identify and change thought patterns related to hoarding behaviors. Exposure therapy, a component of CBT, gradually exposes individuals to discarding items.

Family therapy sessions educate loved ones about the disorder and teach them how to provide effective support. This approach helps improve family dynamics and reduces conflicts related to hoarding behaviors.

Community Resources

Local mental health clinics often offer specialized programs for hoarding disorder. These programs provide comprehensive assessments and treatment plans.

Social services can assist with home organization and decluttering. Some communities have task forces dedicated to helping individuals with hoarding tendencies maintain safe living conditions.

Professional organizers trained in working with hoarding disorder can offer practical assistance. They help create manageable organizational systems tailored to the individual's needs.

Local fire departments sometimes provide home safety inspections, identifying potential hazards related to excessive clutter.

Prognosis and Outcomes

The prognosis for hoarding disorder varies based on several factors. Early intervention and consistent engagement in therapy often lead to better outcomes.

Treatment response can differ among individuals. Some may show significant improvement, while others may experience more persistent symptoms.

Severity of hoarding behaviors impacts prognosis. More severe cases typically require longer treatment durations and may have a more guarded outlook.

Motivation for change plays a crucial role. Individuals who actively participate in treatment tend to have more favorable outcomes.

Access to appropriate treatment is essential. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) specifically tailored for hoarding has shown promising results.

Comorbid conditions can affect prognosis. Depression, anxiety, or other mental health issues may complicate treatment and recovery.

Family support and a stable living environment can positively influence outcomes. Social connections often aid in maintaining progress.

Relapse prevention strategies are important. Ongoing support and periodic check-ins can help sustain improvements over time.

While complete remission may not always be achievable, many individuals can experience significant reduction in hoarding behaviors and improved quality of life through proper treatment and support.