Exploring Hoarding Disorder Opposite: The Struggles of Compulsive Decluttering

While hoarding disorder is widely recognized, there exists a less-known condition on the opposite end of the spectrum: compulsive decluttering. This behavior involves an excessive need to eliminate possessions, often resulting in living spaces that appear empty and devoid of personality. Compulsive decluttering is classified as a type of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and can significantly impact a person's daily life and well-being.

People with compulsive decluttering tendencies may experience intense anxiety or discomfort when surrounded by objects they perceive as unnecessary. They may constantly purge their belongings, struggle to keep even essential items, and feel overwhelmed by the presence of what others consider normal amounts of possessions. This condition can lead to strained relationships, financial difficulties, and emotional distress.

Recognizing compulsive decluttering as a genuine mental health concern is crucial. The cultural embrace of minimalism and decluttering trends can sometimes make it challenging for individuals with this condition to seek help or have their struggles taken seriously. Understanding the differences between healthy organization habits and compulsive decluttering can help those affected receive appropriate support and treatment.

Defining Hoarding Disorder

Hoarding disorder is a mental health condition characterized by persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions. Individuals with this disorder experience distress at the thought of getting rid of items, regardless of their actual value.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) officially recognizes hoarding disorder as a distinct condition. It typically involves:

• Excessive acquisition of items • Difficulty organizing possessions • Cluttered living spaces that impair daily functioning • Significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of life

People with hoarding disorder often have strong emotional attachments to their belongings. They may feel a need to save items for future use or fear losing important memories associated with objects.

The prevalence of hoarding disorder is estimated to be around 2.3% of the population. It usually emerges later in life, with an average age of diagnosis around 40 years old.

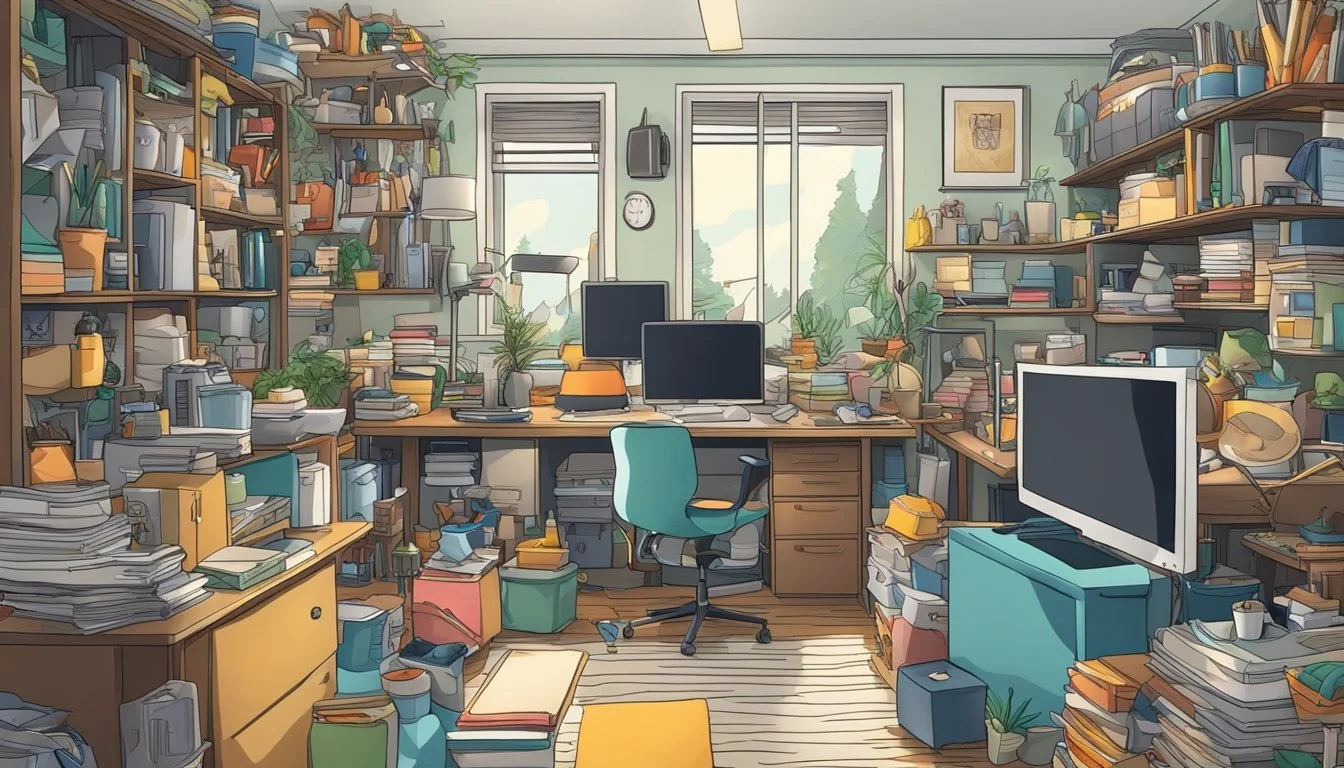

Hoarding behaviors can range from mild to severe. In extreme cases, living spaces may become unusable or even uninhabitable due to the excessive accumulation of items.

Understanding Hoarding Disorder

Hoarding disorder is characterized by persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of their actual value. Individuals with this condition experience significant distress when attempting to get rid of items.

The disorder leads to the accumulation of excessive quantities of belongings, often cluttering living spaces to the point of impaired functionality. This can create health and safety hazards in the home.

People with hoarding disorder typically display:

Strong urges to save items

Intense anxiety about discarding possessions

Difficulty organizing and categorizing belongings

Indecisiveness about what to keep or discard

The items hoarded may include:

• Newspapers and magazines • Clothing • Books • Household goods • Sentimental objects

Hoarding behaviors often begin in adolescence or early adulthood, gradually worsening over time if left untreated. The condition can severely impact a person's quality of life, relationships, and daily functioning.

While once considered a subtype of OCD, hoarding disorder is now recognized as a distinct condition in the DSM-5. Treatment typically involves cognitive-behavioral therapy, addressing underlying beliefs about possessions, and developing organizational skills.

Conceptualizing the Opposite of Hoarding Disorder

The opposite of hoarding disorder involves a strong drive to eliminate possessions and maintain minimal belongings. This tendency manifests in two main forms: minimalism and uncluttering.

Minimalism

Minimalism emphasizes living with fewer possessions and focusing on what's essential. Practitioners aim to reduce clutter and simplify their lives by owning only items that serve a clear purpose or bring joy.

Some key aspects of minimalism include:

Curating belongings to keep only the most meaningful or functional items

Adopting a "less is more" mindset

Regularly evaluating possessions and removing unnecessary items

Prioritizing experiences over material goods

Minimalists often report feeling less stressed, more focused, and having increased mental clarity. However, taken to extremes, minimalism can become rigid or impractical.

Uncluttering

Uncluttering involves actively removing excess items from one's living space. It focuses on creating organized, tidy environments by systematically reducing possessions.

Common uncluttering practices include:

Regularly decluttering spaces like closets, drawers, and storage areas

Implementing organizational systems to maximize space

Donating or discarding items that are no longer needed or used

Setting limits on new purchases to prevent accumulation

Uncluttering can lead to more efficient use of space and easier home maintenance. In some cases, it may develop into compulsive decluttering, an excessive need to purge possessions that can interfere with daily life.

Psychology of Accumulation and Disposal

The psychology behind accumulating and disposing of possessions involves complex emotional attachments and decision-making processes. These factors shape how individuals interact with their belongings and environment.

Attachment to Possessions

People form emotional connections to objects for various reasons. Some items hold sentimental value, representing memories or relationships. Others provide a sense of security or identity.

Excessive attachment can lead to difficulty parting with possessions, even those with little practical use. This behavior is often rooted in fear of loss or change.

For some, accumulating items becomes a coping mechanism for anxiety or past trauma. The act of acquiring new things may temporarily boost mood or fill an emotional void.

Disposal of Items

Deciding to discard possessions can be challenging for many individuals. The process involves weighing practical considerations against emotional attachments.

Some people experience anxiety or distress when faced with decluttering tasks. This reaction may stem from fear of making wrong decisions or losing important memories.

Cognitive biases can influence disposal choices. The endowment effect, where people overvalue items they own, often makes parting with possessions more difficult.

Successful decluttering often requires developing new mental frameworks. This might involve reframing the value of items or focusing on the benefits of a less cluttered space.

Behavioral and Emotional Aspects

Individuals with hoarding disorder's opposite exhibit distinct behavioral and emotional patterns. These patterns manifest in compulsive decluttering tendencies and a unique relationship with possessions.

Compulsive Decluttering

Compulsive declutterers feel an overwhelming urge to minimize their belongings. They experience anxiety and discomfort when surrounded by objects, leading to frequent purging of possessions. This behavior can result in discarding useful or sentimental items.

Unlike hoarders, declutterers struggle to keep things, even necessities. They may repeatedly reorganize spaces, seeking a perfect, minimalist environment. This pursuit of order can interfere with daily life and relationships.

Emotional responses often include relief after discarding items, followed by regret or panic. Some individuals report feeling "lighter" or less burdened after decluttering sessions.

Indifference to Possessions

Those with the opposite of hoarding disorder display a marked lack of attachment to material goods. They often struggle to form emotional connections with objects, viewing them as disposable or easily replaceable.

This indifference extends to gifts, heirlooms, and personal mementos. Individuals may discard items without hesitation, regardless of monetary or sentimental value. They prioritize space and orderliness over keeping possessions.

Emotionally, they may feel detached from their surroundings and struggle to create a sense of "home." This can lead to challenges in maintaining a comfortable living environment and difficulty relating to others who value material possessions.

Manifestations and Comparisons

Compulsive organizing and difficulty deciding what to keep are key aspects of hoarding disorder's opposite manifestations. These behaviors can significantly impact daily life and relationships.

Compulsive Organizing

Individuals with compulsive organizing tendencies often experience intense anxiety about clutter or disorganization. They may spend excessive time arranging items in precise ways or creating complex organizational systems. This behavior can lead to perfectionism and difficulty completing tasks.

Compulsive organizers might feel a strong need to maintain strict order in their living spaces. They may become distressed if objects are moved or their systems are disrupted. This can strain relationships as family members struggle to meet their high standards.

Some people with this trait may constantly reorganize their belongings, feeling that no system is ever quite right. This perfectionism can paradoxically lead to less functional spaces as the focus shifts from usability to perceived orderliness.

Deciding What to Keep

People with extreme decluttering tendencies often struggle to decide what items to keep. They may experience anxiety about possessing too many things, leading to excessive purging of belongings. This behavior can result in discarding useful or sentimental items.

These individuals might set rigid rules about what they allow themselves to own. For example, they may limit themselves to a specific number of clothing items or books. This can lead to impractical situations where necessary items are discarded to maintain arbitrary limits.

The decision-making process can be emotionally draining for those with this trait. They may spend hours deliberating over each item, feeling overwhelmed by the perceived burden of ownership. This can result in avoiding acquiring new things, even when needed.

Treatment Approaches

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the primary treatment for hoarding disorder. This approach helps individuals modify beliefs and behaviors related to acquiring and keeping items.

CBT for hoarding typically involves:

Challenging unhelpful thoughts about possessions

Practicing decision-making and organizing skills

Gradually exposing patients to discarding items

Medication may be prescribed in some cases, especially if depression or anxiety are present alongside hoarding behaviors.

Home visits by therapists can be beneficial, allowing for real-world practice of decluttering techniques. Group therapy sessions provide peer support and shared learning experiences.

For severe cases, a team approach may be necessary. This can include mental health professionals, professional organizers, and cleaning services working together.

Family involvement is often crucial. Loved ones can provide emotional support and practical assistance during the treatment process.

Treatment plans are tailored to each individual's needs and may evolve over time. Progress is typically gradual, requiring patience and persistence from both the patient and treatment team.

It's important to note that forced cleanouts are generally discouraged. These can be traumatic and may worsen hoarding behaviors in the long run.

Case Studies and Personal Narratives

Compulsive decluttering, the opposite of hoarding disorder, often goes unrecognized. While not officially classified in the DSM, it can significantly impact individuals' lives.

Keith's Story, highlighted in documentary filmmaking, offers a glimpse into the personal struggles of those with hoarding tendencies. This narrative approach helps viewers connect with the human side of the disorder.

Dr. Gary Patronek's research provides critical insights into animal hoarding. His work examines the psychological patterns associated with this specific form of hoarding behavior.

Real-life case studies demonstrate how hoarding affects individuals and their families. These stories reveal the complex interplay of psychological, genetic, and environmental factors contributing to the disorder.

Some documentaries explore the journey from clutter to clarity. They showcase individuals working to overcome their hoarding tendencies, offering hope and practical strategies for recovery.

Personal narratives often highlight the decision-making difficulties faced by those with hoarding disorder. These accounts illustrate the challenges in processing information and letting go of possessions.

By sharing lived experiences, these stories help reduce stigma and promote understanding. They demonstrate that hoarding is a complex issue requiring compassion and professional support.